Why Calm Conditions Require a Different Method

Without wind or current pushing your hull, you have complete control over your boat’s movement. This absence of external forces is a great advantage. It also means you are solely responsible for every motion. Every adjustment to your throttle or steering directly influences your path.

The two factors you must command are momentum and your boat’s pivot point. Your boat will continue moving in a direction long after you cut the power. Understanding this inertia is central to a smooth docking experience.

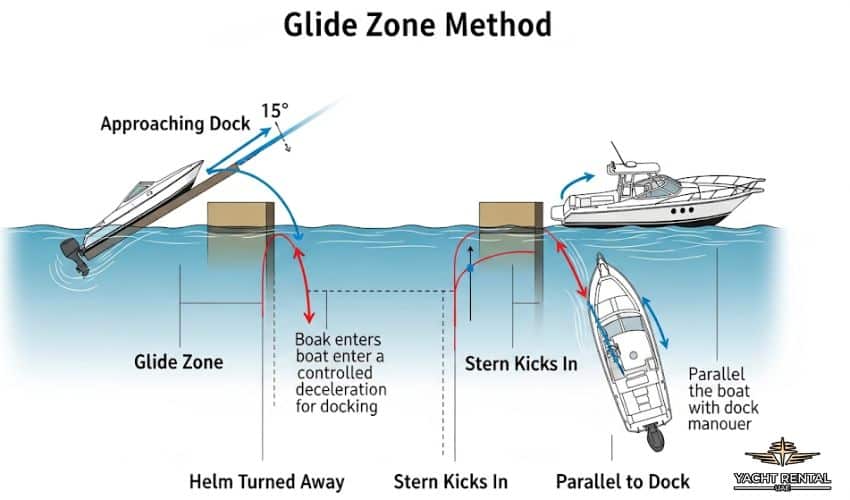

The “Glide Zone” Method

This technique works for most single-engine and twin-engine powerboats. It is built on the principle of using minimal power and letting the boat’s glide do most of the work.

Step 1: Plan Your Approach

Before you get anywhere near the dock, preparation is essential. A rushed approach is often a failed one.

- Ready Your Gear: Pull your fenders out and hang them at the correct height for the dock. Place your bow, stern, and spring lines on the side you will be docking, ensuring they are coiled neatly and will not tangle.

- Brief Your Crew: If you have help, assign one person to the bow line and one to the stern line. Instruct them not to jump off the boat until you give the command. Their job is to gently loop the lines over dock cleats.

- Establish Your Glide Zone: Identify a spot about two to three boat lengths away from your final docking position. This area is your “Glide Zone.” Here, you will shift into neutral and perform most of the maneuver without constant engine power.

Step 2: The Slow Approach (10-15 Degree Angle)

Your goal is to approach the dock at a shallow angle, around 10 to 15 degrees. A steep angle forces an aggressive, last-second turn. A shallow angle gives you time and space to make small corrections. Control your speed by shifting in and out of gear. Instead of maintaining a low RPM, give the engine a short “bump” in forward gear, then shift to neutral. Let the boat glide. This prevents you from building too much speed and allows for precise adjustments. You want to be moving at a slow walking pace or less.

Step 3: Entering the Glide Zone and Using the Commitment Point

As you enter your pre-determined Glide Zone, shift the engine into neutral. Your boat will now be gliding toward the dock. This is the moment to assess your speed and trajectory. Think of the start of the Glide Zone as your Commitment Point. This is the last safe position to abort the docking and circle around for another try.

- Too Fast? Give a short bump of reverse gear to slow your forward momentum.

- Too Slow? A quick, short bump of forward gear will add just enough momentum.

The key is small, deliberate inputs. Avoid the temptation to stay in gear.

Step 4: The Final Turn and Securing the Boat

Here is the part that feels counter-intuitive to many new boaters. As your bow nears its target point on the dock, turn your steering wheel away from the dock. On most powerboats, the pivot point is roughly one-third of the way back from the bow.

When you turn the wheel away from the dock, the bow will swing slightly out, but the stern will “kick” in toward the dock. This powerful turning force will bring your boat perfectly parallel to the dock. Once parallel and stopped, have your crew lightly toss the bow line over a dock cleat. Securing the bow line first stops all forward motion and fixes your pivot point. Then, secure the stern line to keep the back of the boat from drifting out.

Common Mistakes in Calm Water Docking (And How to Fix Them)

Even in perfect conditions, simple errors can make docking stressful. Knowing these common pitfalls is the first step to avoiding them.

| Mistake | Why It Happens | The Fix |

| Too Much Speed | Overconfidence or misjudging the boat’s glide. | Approach slower than you think is necessary. Use neutral generously. Your final approach speed should be less than a slow walk. |

| Over-Steering | A natural reaction to seeing the boat drift, causing a panic-induced correction. | Make small, deliberate steering adjustments early in the approach. Trust the boat’s glide and pivot. |

| Improper Line Handling | Rushing the final moments, tangled lines, or unprepared crew. | Prepare all lines and brief your crew before starting the approach. Everything should be ready to go. |

| Forgetting the Pivot | Focusing only on getting the bow close to the dock. | Practice the “stern kick” in open water. Get a feel for how your boat pivots when you turn the wheel at slow speeds. |

Powerboat vs. Sailboat Considerations

While the principles are similar, different boat types have unique behaviors.

Single-Screw Powerboats: These boats exhibit “prop walk.” In reverse, the stern has a tendency to move sideways. A right-hand propeller (which spins clockwise in forward) will typically walk the stern to port (left) in reverse. According to BoatUS, you can use this to your advantage. For a port-side tie-up, a bump in reverse will slow you and pull the stern nicely toward the dock.

Sailboats: With their deep keels and high sides, sailboats carry significant momentum and can be surprisingly affected by even the slightest air movement. The keel provides a very stable pivot point. An even slower, more deliberate approach is required. The “glide” phase is much longer on a sailboat.

Using a Spring Line for Control

For ultimate control, especially when docking alone, a midship spring line is an excellent tool.

- Rig a line from a cleat near the middle of your boat.

- As you come alongside the dock, have the line ready.

- Loop the end of the line around a dock cleat that is slightly behind your boat’s midship cleat.

- Put the engine in forward gear at idle speed with the wheel turned slightly away from the dock.

The tension on the spring line will stop the boat’s forward motion and pull the stern gently into the dock. This holds the boat securely in place while you handle the bow and stern lines.

Also Read: Your Boat Gets Swamped Far From Shore. What Should You Do

Final Words About Docking Your Boat

True mastery of docking is not about force; it is about feel. After dozens of landings, you begin to sense the boat’s momentum as an extension of your own body. You learn to anticipate the glide and the pivot. The goal is to arrive so gently that your fenders barely compress.

Calm, windless days are not just easy; they are the perfect classroom. Use them to practice these slow-speed maneuvers until they become second nature. The confidence you build in these ideal conditions will serve you well when the wind and current inevitably return.